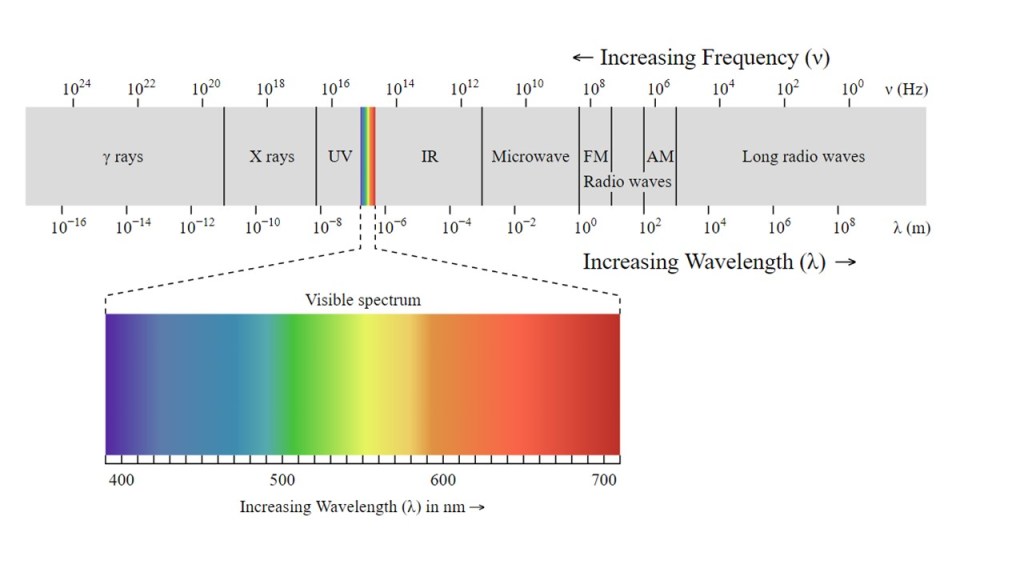

As illustrated by the following diagram, visible light is just a small part of the electromagnetic spectrum. The range of electromagnetic energy we can see is a function of the structure of human eyes. Other animals, ranging from bees to reindeer, can see ultraviolet light (to the left of the color bar). In a similar manner, creatures such as snakes, bats, and mosquitoes can see infrared light (to the right of the color bar).

Note that “nm” in the figure is an abbreviation for “nanometer” which is one billionth of a meter. Light travels as waves like the waves on the ocean. The distance between successive waves is the wavelength.

I decided to experiment with digital photography beyond the visible spectrum. This requires specialized cameras, lenses, and lens filters.

Standard cameras have built in sensor covers that block ultraviolet (UV) and infrared (IR) light. The covers must be replaced with “clear” ones to use them for UV-IR photography. This typically costs around $250 and requires sacrifice of a donor camera. I had planned to do this but then found an old Fujifilm IS Pro (//en.wikipedia.org/wiki/FinePix_IS_Pro) — specially designed for UV-IR — on eBay for $250. It was completely bare when I bought it (no batteries, memory card, charger, lens, filters, body cap, strap, or eyecup) but it was still a bargain.

After I ordered the camera, I needed a lens. Most lenses have coatings that block UV light. The best solution is a lens with quartz elements. Unfortunately, those cost between $6000 and $9000. The second-best solution is a glass lens which is so cheap that the UV coating is omitted. I found several websites that discuss that type of lens. One of the best is //kolarivision.com/uv-photography-lens-compatibility. Based on the online advice I purchased a used Nikon 50mm f/1.8D (i.e., a nifty fifty) lens from Adorama for about $80.

With the Fujifilm and the lens, I had an extended range camera. The images it made included light energy from the visible spectrum plus UV and IR. I needed filters. There seemed to be many reasonably priced IR filters but UV filters are expensive. Among the handmade Christmas ornaments and other flotsam on Etsy, I found a store called UVIROptics which makes custom filters at a reasonable price. I ordered four: (1) one which passes UV and IR but blocks visible light; (2) one which blocks IR but passes visible light and IR; (3) one which blocks all light except near-IR and IR; and (4) one which passes IR light but blocks all visible light. For those keeping score, these are a Hoya U-360, a Schott S8612, a Schott RG715, and a Schott RG850, respectively. With these, I can block visible light and choose the portion of the non-visible spectrum I wish to photograph.

I got the other parts I needed for a complete system and decided to experiment. For a reference, I photographed these flowers in visible light.

Flowers in visible light

After taking the reference photo, I screwed the near-IR plus IR bandpass filter (the Schott RG715) onto the lens and took the following photograph. The red coloring comes from the portion of the visible spectrum just before IR that this filter allows to pass. Note that the 715 portion of the filter name indicates that it blocks light whose wavelength is less than 715 nm. This is at the far right of the spectrum chart at the beginning of this post.

Passing wave lengths greater than 715nm

Something I almost immediately learned is that it is very difficult to focus a camera outside the range of visible light. IR and UV spectra have different focal points than visible light on the same lens. Some lenses have markings for IR focusing. I have never seen a lens with markings for UV focusing. For me, that didn’t matter since my lens only has markings for visible light. My camera has a basic liveview capability but it is difficult to invoke (you must press three buttons) and it isn’t very clear. I started a “shoot-and-pray” strategy when I realized that I could find focus using visible light and then focus bracket around that and then use Photoshop to focus stack the images. That works pretty well.

In my second experiment, I used the “IR-only” filter (the RG850). This is the image I got after stacking.

Passing wavelengths greater than 850nm

The color cast on this image tells me that some visible light is passing through the filter but the overall image seems pretty good.

In my final experiment, I blocked both visible and IR light by stacking the Hoya U-360 and the Schott S8612. This is the equivalent of a 10-stop filter. I had to increase my exposure time from fractions of a second to 25 seconds and use a 865 nm UV flashlight ($35 on Amazon) to light paint the flowers. I got the following photo after focus stacking.

I want to try some new images in the coming week. My inspiration for this is Craig Burrows. I hope to grow some of the plants he mentions in his website to use in photography in the spring.

So glad you are having fun and building and learning 😀

LikeLike

Thank you! I am trying to maintain my sanity during Covid and the election 🤪

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good. Even in Australia it’s hard to escape the craziness of US politics 🙄

LikeLike